A Neurobiology Of Sensitivity? Sentience As The Foundation For Unusual Conscious Perception

A Neurobiology of Sensitivity? Sentience as the Foundation for Unusual Conscious Perception

From: http://sci-con.org/2007/01/a-neurobiology-of-sensitivity-sentience-as-the-foundation-for-unusual-conscious-perception/

Jan 17, 2007

Consider the following scenario. A man – let’s call him Todd – is beset by what he calls ‘visions’ over a nearly 24-hour period. He sees a figure struggling at the bottom of a ravine, fighting for life. The visions are clearly not dreams, nor are they part of normal wakeful awareness. Todd does his best to ignore the stimuli but they will not go away. Rising for work after a restless night, he drives down the road with his twenty-something son in the front seat. A scant mile or two away, he sees a damaged guardrail by the side of the road and asks his son, “Did you hear any ambulances last night?” The son replies no, and the father decides to investigate. At the bottom of the embankment, in a shallow creek and partially camouflaged, lies an SUV with its driver inside, critically injured. Thankfully, he is rescued in short order and recovering as I write this. Can a sentient human being, with a given genetic inheritance and set of life experiences, become conscious in a way that differs markedly from the day-to-day awareness of most people? Todd, who I interviewed as part of a survey on unusual experiences, has not always been plagued by visions. But they have recurred often enough over the past 20 years to give him pause. He was one of ten children who grew up with an alcoholic, abusive father. He is the only sibling who harbors these lifelike, occasionally precognitive visions. He also reacts adversely to many everyday chemicals, sometimes becoming dizzy or disoriented at work. Additionally, he claims to have suffered two major electrical shocks in his life. Intriguingly, his eldest daughter – who survived her own life threatening automobile accident—is apparently affected by ‘visions’ as well. Hours before Todd set off for work that morning, she called him to say that she’d seen him at the bottom of a creek, making his way through brambles. Ever since her accident, this daughter has also been affected by severe migraine headaches.

What is going on here? Are Todd and his daughter delusory? Fantasy-prone? What link, if any, can be hypothesized with such physical concomitants as migraine and chemical sensitivity? Is it possible that the individuals we’re tempted to write off as either highly imaginative or emotionally overwrought (or both) offer a living laboratory wherein we can forge a better understanding of the sensory components of anomalous perception? Last but not least, could study of these exceptional cases add to our knowledge of sentience itself and the mechanisms whereby raw sensation is transmuted into conscious awareness?

Over ten years of collecting such reports and systematically surveying the people involved, I have come to suspect that a ‘neurobiology of sensitivity’—combining elements of nature as well as nurture—explains these odd perceptions better than the old standbys magical thinking, gullibility, hypochondria, self-deception or outright deceit. Clearly individuals who regard themselves as anomalously sensitive could be victims of their own internal con job, courtesy of a well-oiled imagery apparatus that kicks into gear through the mechanism of dissociation. But it is worth considering whether some of these people, at least, might be reacting to genuine external stimuli—much as a person with a migraine headache may react to lights, sounds, smells, or changes in barometric pressure. In that sense, what we marginalize as ‘extra’ sensory may not be so. It may, instead, constitute a highly refined capacity to fix on a range of stimuli that never really registers with the rest of us.

Individuals surely differ considerably in the amount and kind of sensory information they overtly react to. My question is this: can a sentient human being, with a given genetic inheritance and set of life experiences, become conscious in a way that differs markedly people with a ‘sensitive’ personality type are far more likely to report anomalous experiences from the day-to-day awareness of most people? This is precisely what happens with synesthesia (overlapping senses, such as hearing colors or tasting shapes): certain people do perceive the world quite differently, and from an early age. Why are they synesthetic and others not? For that matter, some people will swear that they perceive their surroundings—or themselves—much differently under hypnosis. Before the advent of MRIs and other forms of advanced brain scan technology, it was easy to ignore or deride such reports. Now we realize they have a bona fide neural basis.

Could anomalous perceptions, which have persisted across societies and throughout history, have a similar legitimacy? And, if so, what would we stand to learn about perception itself, or memory, or imagination, or empathy, or any of the myriad of other factors that make us human?

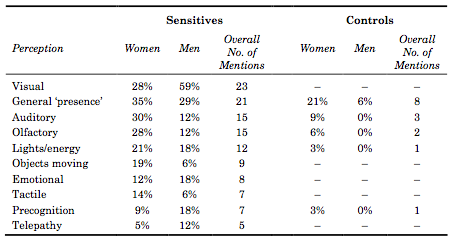

My own investigation—published via papers in the journals Seminars in Integrative Medicine and, yes, the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research (one has to start somewhere)—suggests that people with a ‘sensitive’ personality type are far more likely to report anomalous experiences. Such persons commonly report longstanding allergies, chronic pain and fatigue, depression, migraine headaches, or sensitivity to light, sound, and smell. These individuals are also more likely to report that immediate family members suffered from the same conditions, raising the nature-nurture question in an altogether fresh venue.

My thesis came together gradually, and from a most unlikely source. In the course of my job at the time—which involved developing indoor air quality guidance for the nation’s commercial building owners and managers—I was researching so-called Sick Building Syndrome and another poorly understood condition called Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. (In the former, groups of people feel unwell inside buildings for no immediately discernable reason; in the latter, people claim to be allergic to trace amounts of chemicals, aromas, even electricity.) I read various accounts and went on to speak with people who said they were affected by these conditions. Rather than chalk up their complaints to a hyperactive imagination or some shade of mental illness, I suspected they might have a threshold sensitivity much lower than average. When several individuals confided to me that they’d had apparitional experiences, the wheels started turning. Since then, I have delved deeply into the possibility that a variety of odd sensitivities may have a common neurobiological foundation—stemming at least as much from the body as the brain.

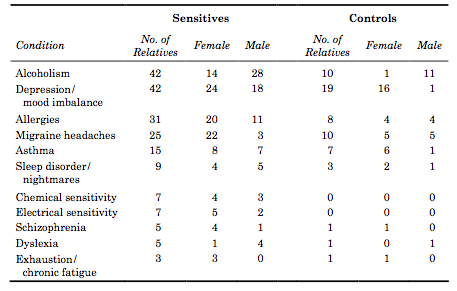

The survey I constructed drew 62 self-described ‘sensitives’ along with 50 individuals serving as controls who did not profess any outstanding forms of sensitivity. Persons in the former group were 3.5 times as likely, on average, to assert that they’d had an apparitional experience (defined as perceiving something that could not be verified as being physically present through normal means). Sensitive persons were also 2.5 times as likely to indicate that an immediate family member was affected by similar physical, mental or emotional conditions.

Overall, 8 of the 54 factors asked about in the survey were found to be significant in the makeup of a sensitive personality:

- Being female

- Being a first-born or only child

- Being single

- Being ambidextrous

- Appraising oneself as imaginative

- Appraising oneself as introverted

- Recalling a plainly traumatic event (or events) in childhood

- Maintaining that one affects—or is affected by—lights, computers, and other electrical appliances in an unusual way.

Interestingly, synesthesia (a condition I was not familiar with at the outset of the project) was reported by approximately 10% of the sensitive group but not at all among controls. This finding gives added weight to the possibility that anomalous perception stems from an inherited neurobiology—as does the striking result that 21% of sensitives reported being ambidextrous against just one individual in the control group. However, a sensitive neurobiology could be conditioned as easily by nurture as by nature. To wit: recall of a traumatic event in childhood was indicated by a majority of sensitives (55%), as contrasted with less than a fifth of controls (18%). Furthermore, a startling 14% of sensitives reported having been struck by lightning or suffering an electrical shock (remember Todd at the beginning of this article?), whereas none of the control group checked this item.

Evidence is steadily accruing across the sciences that certain individuals are, from birth onward, disposed to a number of conditions, illnesses, and perceptions that, in novelty as well as intensity, distinguish them from the general population. If this is indeed the case, anomalous experience may have a bona fide neurobiological basis that (finally) makes it accessible to scientific inquiry. We may also have a means – through these quite remarkable people – of furthering our understanding of the sentient base that conscious awareness is built upon.